For the last few years, friends and colleagues have been asking me to clarify the matter of the sheer quantity of Malewicz (Kasimir Malevich) attributions. Some of these attributions are related directly to my Catalogue Raisonné (Paris, 2002). Others pertain to the endless tide of recent imitations. I have long preferred to devote my energy and time to productive work rather than to polemics, most of them sterile, as they are put forward for specious reasons (to say the least). The fight for the survival of Aleksandra Exter’s oeuvre further burdened my workload and meant that I was faced with severe choices.

I’ll abstain from commenting on the fanciful attributions accompanying the detestable flood of fakes on the art market since the late 1980s (most recently in Tours in 2009 and Ghent in 2017-2018). Nor will I say anything about studies deliberately based on fallacious interpretations (whether mathematical, “scientific” or other). I also choose to ignore the self-proclaimed experts prompted by basement-level commercial concerns who have never held a genuine Malewicz painting in their hands and who blather on in an indecent but obviously self-serving manner. Let others judge them.

The publication of my Catalogue Raisonné, I must note, had a perverse result insofar as it included a list of lost and/or destroyed works, accompanied thanks to my research by precise historical references. These have facilitated the more or less recent production of a number of paintings based on the images I supplied. Thus, several works I had described as “lost” turned up suddenly and miraculously. I’ll also ignore certain jejune imitations, like the works on paper ascribed to Malewicz’s close friends or favourite students, which a low profile merchant presented only weeks ago at the 2018 Foire de Paris. The forger had not even taken the trouble to age the paper !

The present comments are limited to criticism of my Catalogue Raisonné, to which I added a study of Malewicz’s painting technique. Originally compiled for the catalogue, this text, which the Paris publisher dropped at the last minute due to considerations of space (i.e. budget) , was published in French five years later as chapter 31 of the fourth volume of my monograph Kazimir Malewicz, le peintre absolu (Thalia Edition, Paris, 2007) and in English in Artibus et Historiae, vol. 57 (2008) [1]. Not long ago I had the pleasure of learning that this text had been favourably reviewed in the eminent British review ArtWatch UK [2].

The criticism I address here is the one leveled by Troels Andersen, one of the pioneers — but not the only one — of Malewicz scholarship in the 1960s. In his book The Leporskaya Archive (Aarhus University Press, Aarhus 2011), Andersen makes the ex cathedra pronouncement, as if this were a clearly established fact beyond all possible discussion, that a number of drawings and paintings in my catalogue are not genuine works by the artist. However, in a substantial number of cases the documents upon which my attributions are based contradict Andersen’s edicts. Like a number of my colleagues in museums, after recently being again stonewalled by the author, I regretfully find myself obliged to rectify his remarks, unfortunately in writing and with no prior discussion. A recent case whose ramifications seem to plunge in the murky waters of the market for fakes compels me to return to—and to extend—the explanations I developed at the time I was working on my Catalogue Raisonné. I intend to do so, if only indirectly, in a forthcoming publication [3].

* * *

To begin with, let me recall that aside from public and private archives and collections (for example, a number of Hans von Riesen’s personal papers not included in the repository of documents acquired by Amsterdam’s Stedelijk Museum), my work is based primarily on a physical examination of the paintings in question, this with reference to indisputably genuine works, as well as on the inventory of the remains of Malewicz’s studio drawn up by his student Nikolai Suetin and, after the latter’s death in January 1954, by his companion Anna Aleksandrovna Leporskaya (1900-1982). Leporskaya was the master’s informal assistant in the 1920s and a student of his at the Institute of Artistic Culture (GINKhUK) in Leningrad. I am indebted to her for important details concerning Malewicz’s painting practice and his method of classifying his drawings, the logic of which she revealed to me one day. She had taken part in cataloguing these, writing Roman letters and numbers on the back of certain drawings under Malewicz’s dictation. In the mid-20s Malewicz undertook a new system of cataloguing his drawings for pedagogical purposes, as a reinterpretation of his development of Suprematism.

The fate of the artist’s archives, which included a large portion of the drawings, has been rather complex, as many documents disappeared in the course of police searches in the fall of 1930 [4] (For example, all the papers connected with the artist’s Polish and German contacts, notably his correspondence with Wladyslaw Strzeminki, Julian Przybos, Tadeusz Peiper and others).

In 1955, Nikolai Khardzhiev took whitout further notice a large portion of the drawings into his personal custody, thereby earning Anna Leporskaya’s lasting enmity. A small quantity of documents, including a few drawings, remained in the hands of the artist’s widow Natalia Andreevna (1902-1990) until her death. Traumatized by Malewicz’s second spell in prison (in 1930), she categorically refused to speak about him up to her dying day [5]. Other documents stayed in the hand of Ilya Chashnik’s widow, Cecilia Grodneva Chashnik (1907-1973). The friendship I enjoyed with Chashnik’s son, also named Ilya (1929-1977), an architect by profession and an intelligent and wonderfully generous person who was totally devoted to the memory of his father and that of Malewicz, helped me considerably find my way through what I termed the “family labyrinth” around Anna Leporskaya, Chashnik’s son and Suetin’s daughter, Nina Nikolaevna (1939-2016), who also happened to be married to Chashnik’s son.

In the introduction to the Catalogue Raisonné, I summarized most of the issues related to Malewicz documents. However, I observe with regret that as a general rule, while the images are viewed, my comments and, still less, my introduction are almost never read.

* * *

Miroslav Lamac (1928-1992), one of the best art historians of his generation and a remarkable connoisseur of Cubism in particular (he wrote several books on this subject), catalogued most of the works that were still in the possession of Anna Leporskaya, as well as those in other Russian collections, prior to late summer 1969. He was one of the first to reveal in an intelligent manner the significance of Suprematism. With the assistance of the Prague photographer Karel Kuklik, he carried out the task of documenting the remains of Malewicz’s (and later Suetin and Leporskaya’s) studio [6].

Besides this major source, other public and especially private collections were photographed by Jan Sagl et Karel Neubert, two Czech photographers who, commissioned by a couple of Prague reviews — Výtvarné práce and Výtvarné ŭmení, directed respectively by Jiri Padrta and Miroslav Lamac — also travelled to the Soviet Union at this time. In 1973, I visited Neubert and was able to view his entire collection of photographic negatives and discover several unknown works by Malewicz, of which I acquired the photographs.

Apart from his skill as a photographer, Kuklik, whose work has been recognized in his own country for decades, a precise man possessing an indisputable moral rectitude and an exacting conscientiousness, had the added benefit of speaking Russian fluently. Hence, he occasionally served as a translator and made it his business not only to photograph the works and documents still in Anna Leporskaya’s keeping at the time, which he did with a remarkable proficiency, but also to catalogue the drawings by noting by hand the details pertaining to them on each small white envelope containing a negative. (These envelopes as well as the negatives are now part of my personal papers).

In the 1980s, I had occasion to meet Kuklik several times in Prague, for from 1979 on (when I began working on both the monograph and the Catalogue Raisonné), he provided me with all the photographs of Malewicz and his students I required. Then he gave the negatives to Miroslav Lamac. In the mid-80s, Lamac, realizing that he was ill and no longer able to carry on his work on Suprematism, handed all his documentation to me. As Kuklik informed me in the course of our last meeting in Prague on 20 November 2012 [7], on Miroslav Lamac’s demand Kuklik had singlehandedly completed the job of photographing and inventorying the last works of Malewicz and his students during the summer of 1969, Lamaxc having by that day left Leningrad for Moscow. He added that, on the day he finished, Anna Leporskaya came to his hotel room to bring him the artist’s last drawings to photograph. In 2012, Kuklik provided me with a great deal of information concerning his work, from the type of camera he had used to the size of the envelopes containing the negatives (7 x 11 cms).

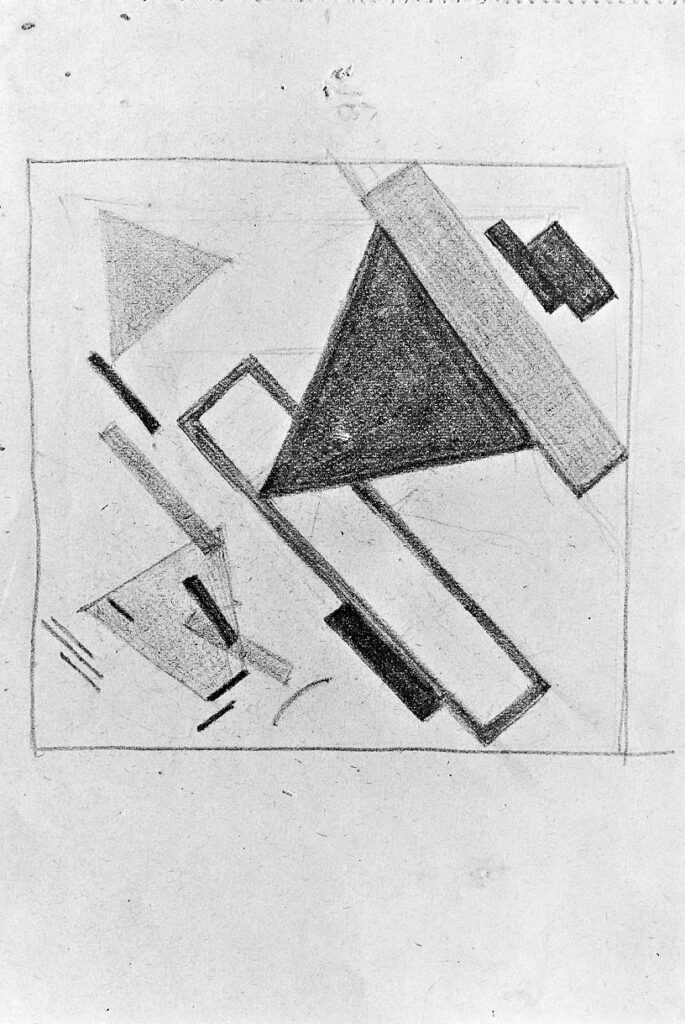

In response to my questions concerning the provenance of several drawings, the photographer categorically confirmed that Anna Leporskaya herself had brought them to him to photograph. I will give just one example: at the end of that last day of work, Leporskaya made him a personal gift of two Malewicz drawings (one in the Suprematist vein, the other Post-Suprematist) and asked him to convey two more Suprematist drawings as a gift from her to Lamac (S-249 in my catalogue) and Padrta (S-110, now in the National Museum in Prague). Both drawings are quite familiar to me, especially S-249 which I often saw in the ‘80s on Lamac’s desk in Prague. (I was able to remove it from its frame, handle it, etc.) Yet both drawings are on the list of works incriminated by Andersen, who states “they are not from Leporskaya’s archive” and, giving no solid documentary or stylistic reason, withdraws them from the inventory of Malewicz’s genuine works.

For that matter, his references to Lamac and Padrta’s trips to Russia (then the USSR) are equally erroneous. Andersen mentions a 1975 letter by Lamac informing him that the Prague art-historian did not think for the time being he would be able to leave Czechoslovakia (as was indeed the case but only after ‘75, not before, for this was when the repression against the “dissidents” in Prague took a tighter turn). The Danish scholar concludes (one wonders why?) that Lamac must have made his last visit to Leporskaya in 1967. However, the information I received from Lamac’s widow, Anna Lamacova, who at my request in 2012 again checked the dates of her former husband’s trip against the stamps in his passport, Miroslav Lamac in fact travelled regularly to the Soviet Union between April 1965 and 1974. Besides other destinations, he visited Leningrad on each occasion (1965, 1966, 1969, 1972, 1973 and the summer of 1974). One can but conclude that Andersen’s information is limited and incomplete and that the inferences he drew need to be revised.

To wind up this discussion of the documents and drawings from Leporskaya’s estate, in 1991, some years after her death and after the sale of the apartment at number 11 Belinski Street where I always used to call on her, the persons taking care of her estate sent for me to sort through the remaining papers and drawings. Toward the end of the winter of 1991-1992, I carried out this work in Leningrad, confined to an apartment and equipped, at my request, with the only object I thought I needed — a photocopying machine. In the course of that arduous week I discovered among various documents and manuscripts a few small Suprematist and Symbolist drawings, gouaches and watercolours I had never set eyes on before. Quite unexpectedly, I also found a number of copies. This turned out to be a valuable lesson in making attributions, which stood me in good stead subsequently [8] for in several cases I was obliged to decide which drawings were by Malewicz and which were by Vera Ermolaeva or Nikolai Suetin. It was a good experience, a matter of arriving at strictly visual choices on the basis of my stylistic knowledge.

In his comments, Andersen defers constantly to Anna Leporskaya’s judgment. I too have a high regard for her indisputable experience, all the more so that she noted her hesitations and occasional changes of mind in writing. I also took note of the fact that she had been introduced to Suprematism at the very time — the mid-1920s — when Malewicz himself was reinterpreting his art, thereby adding a new stylistic level of reflection to his work.

Nor must it be forgotten that in the course of the decades following the master’s death, her way of viewing things lost much of its impact, as happened with many of his other students, owing to the aesthetic censorship of Socialist Realism, a type of painting that contradicted the very premises of modern art and consequently robbed it of a good deal of its legibility. I had occasion to observe this thanks to my contacts with other Malewicz students, such as Lazar Khidekel and Evgenia Magaril, whom I was fortunate enough to interview. My conversations with these witnesses — admittedly at one remove from the master himself — as well as with Nikolai Ivanovich Khardzhiev, an inspired but sometimes tendentious interpreter, cautioned me to make every possible allowance for these visual filters.

* * *

Strangely enough, Andersen says nothing about a body of drawings of dismal quality published by Andrzej Turowski in the Pompidou Center’s magazine in 1987. These drawings had previously gone the rounds of the European art market. Was the scholar’s silence owing to the fact that his name features among the magazine’s “scientific committee” ? Turowski again reproduces these pencil drawings (this time in full colour !) in a volume published in 2004, and again Andersen is silent about this second publication, which I’ll simply describe as bizarre [9].

Another deficiency has to do with stylistic analysis. There is one error among the drawings I attributed to Malewicz in my catalogue. While working quite recently on Lissitzky I realized that I should have assigned it to the latter on stylistic grounds. The work’s provenance was beyond dispute and I had no question as to its authenticity. But I was mistaken in attributing it to Malewicz, for I had blindly accepted all the information the owner had given me. One learns every day.

I will make more information regarding my Catalogue Raisonné available when I finish working on Malewicz’s Red and Black Squares (S-141, formerly in the Hack Collection). I have been familiar with this painting since 1973 and, having had the opportunity to examine it at leisure, have always been convinced it is authentic. But not very long ago it was somewhat surprisingly and, I believe, mistakenly “de-attributed” [10] (Andersen takes the identical position in his 2011 book. I am currently preparing to rebut his argument in detail).

To conclude, I’ll state that, except for a very few exceptional corrections, I still stand by all of the attributions in my 2002 Catalogue Raisonné. In particular I again confirm my attribution of the drawings that Andersen dismisses as being “from Prague drawings.” I have raised the question of their authenticity repeatedly with Lamac, Padrta and, more recently, Kuklik and much earlier with Ila Chachnik’s son, whose memory I cherish, having shared exceptionally moving moments with him in Leningrad in 1976. We discussed the drawings back then, as well as my relationship with Anna Leporskaya. I have followed my friend’s advice.

Herr Schwab, the owner of PVA Verlag in Landau, Germany, a publisher particularly attached to the catalogue raisonné genre, who was initially scheduled to publish my monograph of Malewicz, insisted that I undertake the task of compiling a complete inventory of the master’s work. This long-term endeavour, which underwent an infinite number of stylistic and physical revisions, was eventually published in French some twenty-two years later (2002). As for the monograph it only appeared in 2007. I recall my hesitations at the time, wondering whether I would be capable of carrying out such a difficult the task to the very end. I remember in particular a conversation I had in the early 1980s in Moscow with my friend, the late Wassily Rakitin, one of my few colleagues to engage in the same type of research as me [11]. He answered with the following words: “In ten or twenty years the number of works attributed to Malewicz will have grown several fold, for there will of course be fakes. At present there are no fakes and you have access to the genuine documents concerning the artist’s studio. You must do the job,” he said. Today more than ever I reckon he was right.

_______________________

[1] Andréi Nakov, “Devices, Style and Realisation: Professionalism in Malewicz’s Painting Technique,” Artibus et Historiae, n° 57 (vol. XXIX), IRSA Publishers, Vienna-Cracow, 2008, pp. 183-239.

[2] Alexander Adams, “Malevich’s Restaurations questioned”, ArtWatch UK, No. 28, London, Winter 2012 pp. 19-20.

[3] Announced in the Hack Foundation’s “Lesebrief” in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung , dated 29 November 2017.

[4] If they still exist, the Malewicz files remain inaccessible, as Vitali Chentalinski, a specialist on such matters, confirmed to me in Moscow.

[5] As I myself experienced, having rung at her door in 1998 or in 1989 (?). We had a strange, unforgettable conversation through her closed front door.

[6] Kříž, Jan Karel Kuklík, Prague: České muzum výtvarných uměni (Publications of The Museum of Decorative Arts in the Czech Republic), 1997; also Karel Kuklík. Krajiny návratů (Landscapes of Returns), Prague, 2004.

[7] At my request he certified this in writing, dating it 10 February 2013.

[8] Some of these copies figured (without any indication that they were copies) in a Moscow exhibition in 2002; Aleksandra Shatskikh edited the catalogue. Enlargements of other copies featured recently in another Moscow exhibition.

[9] Andrzej Turowski, Malewicz w Warszawie: rekonstrukcje i symulacje (Malewicz in Warsaw: Reconstructions and Simulations), Cracow, 2002. Though dated 2002, this book was actually published in the spring of 2004, a date that conveniently allowed the Polish author not to mention my Catalogue Raisonné and my “small” monograph Kazimir Malevitch. Aux avant-gardes de l’art moderne (Paris: Editions Gallimard), though he clearly used both volumes in his research.

[10] “Die 50-Millionen Fälschung,” an article signed Peter Brors and Suzanne Schreiber, in Handelsblatt, Nr. 217, Düsseldorf (Germany), 10-12 November 2017, p. 59.

[11] Later, when I was approached at the start of the 1990s with the project of undertaking a similar task as for for Malewicz ‘s oeuvre for this of closest students- Chashnik and Suetin , I convinced Rakitin to take it on, for I knew it was too great for one person alone.

Leave a comment