This exhibition is certainly a milestone in the French recognition of Russian modernism. As such, it is heartily welcome, for ever since the 1979 Paris–Moscou exhibition — to mention only French collections (Mikhail Larionov and Natalya Goncharova, Pavel Mansurov, Ivan Puni [Jean Pougny in French] ), France’s museums have so far kept aloof from the occasionally feverish rediscovery of the Russian avant-garde. For example, Simon Lissim’s proposal for donating a few of Aleksandra Exter’s works to the Musée Nationale d’Art Moderne in 1971 did not even garner a reply… As for theme exhibitions, they never even saw the light of day! With the exception of a Malewicz show in 1978, no major retrospective was organized in France (either for Lybov Popova, Akeksandr Rodchenko, Vladimir Tatlin or Olga Rozanova). Even the Georges Vantongerloo retrospective — an artist who spent a large part of his life in Paris — was held outside of French borders (in Washington and Zurich). The same is true of the more audacious theme exhibitions, unlike those mounted in leading American and non-French European museums.

I prefer not to broach the subject of the recent Shchukin exhibition at the Vuitton Foundation in Paris, which contrary to the historical facts, gave the impression that the Russian Non-Objective avant-garde was initiated by that great modern-art visionary. Not to mention the catastrophic hanging of the show’s second part; the organizers simply neglected to inform visitors that Shchukin never bought Russian avant-garde pictures. All it would have taken to illustrate this fact is to quote from some of Kandinsky’s appalled letters written after his visits to the Moscow collector.

The current exhibition at the Pompidou Center starts out with an extremely satisfying salvo of splendid paintings by Chagall. Unfortunately, as I went deeper into the show, my initial enthusiasm was progressively dampened until I arrived at a final nasty surprise. To begin with, I have trouble agreeing with the idea that Chagall should be given pride of place in the rapid expansion of the Vitebsk art school. Initially, it was El Lissitsky who was responsible for the school’s rise; then, after November 1919, Malewicz. Incidentally, Chagall complained bitterly about Malewicz’s avant-garde impetuosity and proclaimed loudly for decades that he had been “driven out of Vitebsk” by the latter. It’s true that he was made unwelcome there but this was less because of Malewicz himself than because of the revolutionary force of Suprematism, to which many young students adhered enthusiastically.

The thing I found most annoying about the exhibition was its “anecdotal” approach to abstraction. To begin with, I object to the fact that it gave no indication of the stylistic strata of the different periods in the work of El Lissitzky, a remarkable absorber of every modernist trend: the abstract works of his Russian period — Vitebsk and Moscow, 1919-1921 — are combined indiscriminately with works the artist produced in Germany between 1922 and 1925 in a style derived from Western abstract art (Theo van Doesburg and the Bauhaus artists). Yet these are vastly different stylistic developments. I would describe the fact that the exhibition gives not one clue to this fact as an “anecdotal” approach as opposed to “stylistical” one.

Regarding the show’s version of the historical sequence, I would also say that it doesn’t lay sufficient stress to Vitebsk’s rich cultural setting, in particular its musical and Talmudic effervescence (Mikhail Bakhtin) : for example, the city fostered the great pianist Maria Yudina and many others.

Another shortcoming, a much more serious one in my view, is that not once is the geographical expansion (Russian and/or international) of the Vitebsk UNOVIS clearly shown. Yet UNOVIS sections sprang up in Kaluga, Smolensk and Orenburg. (An original, well-documented book devoted to this topic was published more than two years ago; it is not even mentioned in the catalogue.)

As for the city of Smolensk, thanks to Wladyslaw Strzeminski and the action of El Lissitsky, it was the leading conceptual force behind the spread of Suprematism (the first French translations of texts by Malewicz were published in Poland in the mid-1920s). The importance of this European hub for Suprematism’s expansion has been brought to light in the last four decades — since 1973, to be exact — by Polish, German and French art historians (see my texts of 1981 and my Malewicz monograph, 2007/2010). Simply to ignore this scholarship is regrettable, in my opinion. It is also surprising that one of the very few French connections with UNOVIS has escaped the attention of the show’s organizers. In the late 1960s Nadia Leger (née Khodasevich) acquired in Belarus, the country of her birth, a small sketchbook containing Suprematist drawings by a student at the Smolensk UNOVIS (or Minsk UNOVIS? The information I was able to gather in 2000 is contradictory on this point. In any case Nadia Léger claimed the sketchbook as her own work, but that is another matter). For all its modesty, the sketchbook is unquestionably genuine and is an original document relating to Malewicz’s Suprematist teaching at Smolensk. Owing to Nadia Léger’s personality, it played a not inconsiderable part in the French rediscovery of Suprematism. It’s a pity it doesn’t feature in the exhibition and isn’t even mentioned in the catalogue.

In 2000, France’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs sent me to Vitebsk to revive the memory of UNOVIS. Apart from the public classes and official discussions I had occasion to conduct, I was able to consult a large number of archive documents in Minsk, Vitebsk and even Smolensk. Sadly, though, I didn’t notice that the Pompidou Center’s exhibition had made a good choice of these documents. Worse still, most of the documentary photographs on display are reprints of copies. Yet they’re labelled as if they were originals. Why? Their quality is truly dismal. Records of the principal events of the initial period at UNOVIS are missing as well, yet the original photographs and documents are preserved in public archives (the Tretyakov Gallery and RGALI archives in Moscow, the archives of the Russian Museum in St. Petersburg, and those acquired three years ago by a leading American institution).

I was also chagrined to discover that the exhibition includes a number of mediocre canvas by Ilya Chashnik, in spite of the fact that several masterpieces by this artist feature in Western collections (see the catalogue of the latest exhibition I guest curated at the National Gallery of Canada at Ottawa). Incidentally I checked with some of the main collectors in question; none of them had been contacted by the Pompidou Center. It is also unfortunate that a major Suprematist composition by Nina Kogan has not been included in the show, as she was Malewicz’s “painting” assistant at Vitebsk. I recall the incredulity that greeted her work when it was first shown in the West in 1984. There were even people in Moscow and above all New York who claimed that Kogan had never existed… as if time had stood still since Soviet days.

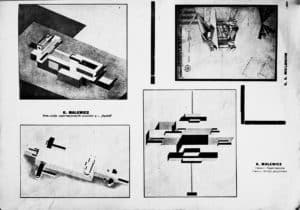

The exhibition’s downside became patent at the end of my visit when I came to the room devoted to architectonas. First of all, very little information concerning this production is supplied and mainly the presentation is once again particularly “unstructured,” if not worse, two (very different) periods of horizontal and vertical architectons being combined in a single mishmash. Yet from 1924 on this aspect of the UNOVIS production was thoroughly documented; the Institute of Artistic Culture (IKhK) even engaged a photographer to record it. And yet what I saw in the exhibition was a large display case filled with pathetic figurines associated with apocryphal fragments of architectons (true, even worse could be seen a few months ago at the Museum of Fine Arts in Ghent, Belgium). The nature of the materials, the proportions and, especially, the figurines that look like miniature garden dwarfs, are in no way like Malewicz’s work of the period. As for the garden gnomes, they are completely foreign to the artist’s architectonic work and, to my mind, have no historical (documentary) basis. I believe I am well introduced in the matter as the estate of Nikolai Suetin, who was in charge of the architectonic workshop at IKhK from early 1924 on, included a number of fragmentary architectons, which I held in my own hands. (At the time they were in the possession of Suetin’s companion, Anna Leporskaya). Other fragments belonged to a private collection to which I also had access. Genuine architectonas are thus far from unknown items; one of them features in the Russian Museum in St. Petersburg, and yet another was found in 1988-89 and is now in the collection of the Tretyakov Museum in Moscow.

After surfacing ten years ago (in 2008) at the Malewicz exhibition in the Vaduz Museum, Lichtenstein, and subsequently in Baden-Baden, Germany, this set of questionable architectons pops up regularly in museum shows without any good reason and mainly unsupported by historical documentation. As I said, neither their materials, nor their proportions, nor the figures populating them, are to be taken seriously. If this were merely an isolated phenomenon, one would expect it to vanish of its own accord (As I did myself for several years). However, other three-dimensional pieces, considerably more voluminous ones, appeared very recently in a Moscow exhibition. That is why I believe it necessary to raise the issue of their attribution. As for the pieces exhibited at the Pompidou Center the most basic precaution would have required that their attribution be followed by a question mark — which isn’t the case.

Banned for decades due to socio-political censorship, the research and presentation of Russian modernism has undergone a veritable renaissance in Russia over the last thirty years. However, in France, with a few notably exceptions, this accelerated rehabilitation has been restricted to a few highly privileged archives. Developing a new way of seeing is another matter. Certain recent developments, such as the research conducted at the Rostov Museum in Russia, give one real hope.

_____________________

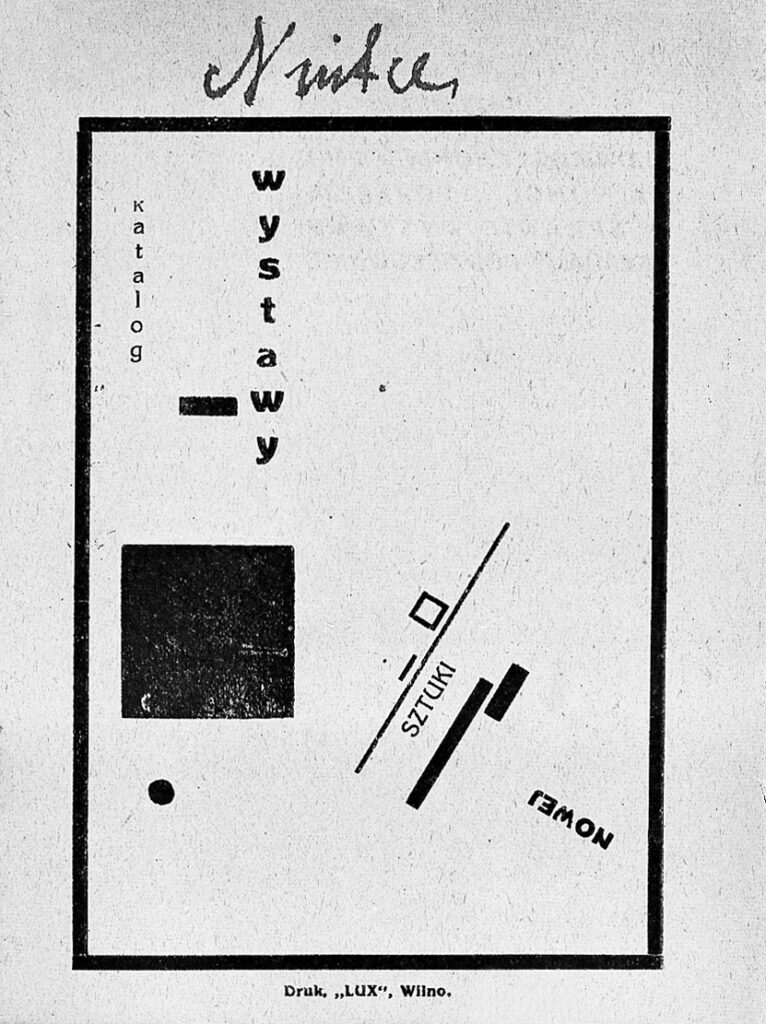

Top illustration

W. Strzeminski, cover of the New Art catalogue, Vilnius, 1923. The design’s composition is directly inspired by the UNOVIS No. 1 anthology, Vitebsk, 1920.